by Gabriella Edelstein & Claudette Palomares

by Gabriella Edelstein & Claudette Palomares

Contents

Introduction: How Far Have We Really Come? by Gabriella Edelstein

Post-script: Sister Suffragette by Claudette Palomares

~

How Far Have We Really Come: Suffragette (2015)

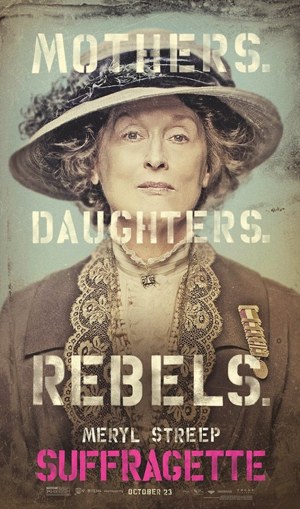

The casting team of Suffragette made a very clever move when they approached Meryl Streep to play the legendary Emmeline Pankhurst. For many, Streep can play anyone and do anything and she will still be faultless. Indeed, I will lap up any Streep film with total unabashed adoration. Furthermore, she has been an ardent and vocal supporter for women’s rights (let’s just forget the fact that she calls herself a ‘Humanist’ instead of a ‘feminist’), and is held up as the bastion of female talent in Hollywood. Thus, in the most ostensible syllogism of 2015, I assumed: if Streep is feminist and playing a famous feminist in Suffragette, then surely Suffragette is a feminist film? Claudette and I found that this was far too convenient of an assumption.

The film tells a story of a group of East End working women’s involvement in the Suffragist movement in 1912. It’s protagonist is Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a washer in an industrial laundry, married to the somewhat hapless Sonny (Ben Whishaw). Through a series of coincidences she meets Violet (Anne-Marie Duff), who brings her into the company of other suffragettes, including Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham-Carter). When she becomes further embroiled within the movement, her husband and community ultimately punish and expel her. Throughout the film, the suffragettes are pursued by Inspector Steed (Brendon Gleeson), who is almost Terminator-like in his lack of empathy and persistence. Besides Streep’s Pankhurst, the only other non-fictional character is Emily Davidson (Natalie Press). For a film intent on telling women’s stories, they made the interesting choice of amalgamating several women for the purpose of narrative convenience.

I keep asking myself whilst watching the film: what was its point? What was its aim? And where does it position itself along the timeline of feminism? Is this a self-congratulatory coda to the movement? A film that says, “It’s okay everyone, we have equal rights in the West so let’s make a movie about the Suffragettes to remember how bad it used to be”. Or, is it meant to inspire further change? I also doubt that it’s meant to be educational, even if it positions itself as a representation of a particular historical moment. It’s especially hard to take that position seriously when its protagonist is a homogenised embodiment of different figures and the film doesn’t give a proper overview of the Suffragette Movement. It’s hardly high art, as Claudette said in our discussion, the filmmaking is just ‘serviceable’. The film doesn’t do much to inspire impassioned rage in its audience, nor does it make us look back and say to ourselves in a grateful tone oh look how far we’ve come when we remember that besides voting rights, things aren’t exactly tickety-boo for women even now.

Ultimately I wonder: does this film even have a reason to exist? It seems to me that Suffragette’s raison d’être is an appeal to the emotions as a way to induce sympathy for the early feminists; it’s an historical melodrama and that’s about it. The force-feeding scene was powerful and reinforced the violence women have experienced in their fight for equality. If that is the only message the film wishes to have, then sure, it succeeds. I think, unfortunately, that the film set itself up with lofty ambitions as a visualised feminist manifesto but was let down by its inability to live up to those expectations. This isn’t the great depiction of the Suffragette movement that I was hoping for, one that would add fuel to the fire of current feminist thinking (and hopefully we won’t have to wait another 100 years before someone has the courage to make another film about a feminist movement).

Despite all this, I would still say that Suffragette is important and worth the watch. Why? Because it inspires us to have these conversations about feminism in the first place. Any film about the fight for freedom and the rights of the downtrodden has value, and this is something we easily forget.

–Gabriella Edelstein, November 2015

~

The conversation

39mins.

GE: So Claudie, did you like movie?

CP: I thought it was a compelling movie when you watch it. Did I like it? I think I did, but I would say that I don’t think it’s a good film.

GE: Why?

CP: The filmmaking is serviceable. I could not think of one shot that I thought “this is beautiful”, or a particular technique that I thought “wow, this is something a bit more creative, a bit more ingenious, a bit more expansive”. I thought it was a pretty by-the-numbers picture. In terms of a historical representation, it ticked all the boxes, but I think there are political films out there that deal with stories in a much more interesting way, whether it’s from multiple perspectives or a non-linear narrative. So that’s why I would say that it’s a serviceable film.

—-

GE: What I find very interesting about this group of women is that they were of a certain class: they’re lower class women, they are workers. So their voice is completely beaten down. There’s a character, Brendon Gleeson, who plays a policeman whose job is to find these women and track them down. And there’s this one moment when he’s talking to Carey Mulligan’s character Maude Watts and he’s saying, Do you think anybody is going to be listening to you? You know what you are, you’re a lower class girl. Do you think that anybody cares? And there’s a truth to that. What I find interesting about this is film is that they’ve made film called: Suffragette, feminism is over, we’ve solved it, well done! But it’s not over. Feminism is not done and I don’t know if the film is supposed to be a coda to that, or if it was made for people to realize that feminism is not over, there’s more that we need to do. So if that was the film’s goal, then I think it failed because I don’t think it was radical enough at all. I felt at the end inspired and sad and completely cynical about the world today, and yet it’s a hundred years later…

—

CP: I don’t see this film doing so well in the American market.

GE: Why?

CP: Because who is your audience? Because you’ve alienated all the feminists who are a lot more aware about representations of people of colour, who will likely boycott this film, so who do you have? On the bus on the way to the Palace Verona, I saw these really striking posters of Suffragette. They were black and white and they were shots of people in the midst of a riot and I can’t remember the tagline but they were very striking. So I think the marketing of the film has been very pro-active about how the film is very engaging but when you see the film, that’s not the reality.

—

CP: I thought maybe we should now turn to the elephant in the room, the film’s critical backlash in terms of its lack of representation of people of colour.

GE: Do I think there should have been women of colour in the crowd scenes? So there’s this scene where the women crowd in the secret of night to see Emmeline Pankhurst on balcony in Bloomsbury. There probably should have been women of colour in the crowd.

CP: In this article in The New Statesman, they have a picture of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, selling a Suffragette newspaper in 1913. So you know that she was there!

GE: The people who made the film could say, well in our defence, we were showing a very small story of working class women that was part of a bigger network but I would argue that that was one of the films flaws. They make it seem like it was these four or five women were the only women who doing something in that movement.

CP: And I think it’s a bit rich to be making a film about inequality without at least trying to establish equality in representation. I think that if you were going to take the moral high ground you –

GE: Gotta go all the way.

~

Post-script: Sister Suffragette

In this week’s conversation, we open with an excerpt from “Sister Suffragette” a song sung by Mrs Banks in the film Mary Poppins (1964). I wanted to include this song as a memorial to the very moment where I was first introduced to the notion of a “suffragette”. In my ten-year old imagination, the notion of the “suffragette” was quite the most alluring idea: women in delightful Edwardian outfits—much preferable to the gargantuan fashions of the Victorians—being clever and singing witty songs about how one loves men individually but as a group they’re “rather stupid”. This radiantly rosy-hued view of history didn’t alter when my next pop-cultural reference for suffragettes came in the beguiling form of Cate Blanchett as Lady Chiltern in An Ideal Husband (1998) (see below for Blanchett’s very smart “suffragette suit”).

Only years later would I realize how utterly I had romanticised the movement. To be fair to my ten-year-old self, both Hollywood and the Period Drama machine that is the BBC has a way of generally eroding the nasty, unseemly bits of history that fail to delight the eye. It was not until high school that I learned the true nature of suffrage: the hunger-strikes, the force-feeding, the suicides-as-a-form-of-protest, and beyond that, the social and economic consequences of a lifetime of disenfranchisement, the ever-present sexual threat and the abject lack of maternal rights. I was yet to discover the sexless, downtrodden creatures that Gabriella recalls so vividly in her own memory. For my own, the glamourous ghosts of Mrs Banks and Lady Chiltern remained.

With its committed portrayal of suffragettes from working-class backgrounds, it is true that Suffragette does present a more nuanced representation of the suffrage movement than its antecedents. But as Gabriella and I explore in our conversation, in the year 2015, is a nuanced representation of class enough? Early critical responses—including our own—seem to conclude on the side of “No. Not nearly enough”.

Much has been written on Suffragette’s seemingly tone-deaf publicity—most infamously, the image of Meryl Streep wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave”. This statement seems particularly crass in the light of the film’s complete lack of women in colour in any of the scenes of the film, not even in the numerous crowd scenes. This has led to some feminist critics such as Ijeoma Oluo refusing to review the film. In response to criticism, the producers of the film have argued that the film is consciously narrow in its scope, representing a small group of women from a very specific background. Indeed, the film really only has four key suffragettess, all except one, fictional composites of real-life women. The great Emmaline Pankhurst is a figurehead rather than a real person, and Meryl Streep’s celebrated casting, a mere cameo, with no more than five or six minutes of total screen-time in the entire film.

In her excellent article What did the suffrage movement in Britain really look like?, Anna Leszkiewicz examines the film’s needlessly compact and ahistorical view of the past. As she explores with a number of academics, there is ample evidence of women of colour within the British Suffrage movement, specifically during the time when the film was set, when the 20th century was just beginning its early teens. In particular, a notable feature of the movement was the involvement of Indian women for whom female emancipation and national emancipation from imperialist subjection were two closely intertwined aims. The most prominent figures of this movement were that of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, Herabai Tata and her daughter Mithan Lam. As Leszkiewicz’s article ultimately concludes, the faces of the British suffrage movement were mostly uniform in colour, but crucially, not always so. The central pre-occupation in our own assessment of Suffragette was whether there the film erred in its lack of representation for women of colour. While we acknowledge that the locus of the film is one specific, working class-woman’s story, Gabriella and I do come to the conclusion that the film’s lack of representation is misguided at best, lazy and narrow-minded at worst.

As with all cultural works that offer pointed political statements, establishing itself as a moral arbiter, it seems hypocritical for a film about the need for equality, to continue to participate in such a predictable mode of exclusion—especially in a time when such omissions are so immediately and palpably felt by a major segment of its audience. What Suffragette’s exclusion of women of colour reveals is a fundamental lack of understanding of audience as well as an ignorance—a refusal to recognize a complex record of marginalisation and misappropriation within the feminist movement that still haunts current advocacy.

Or perhaps Sufragette was created only for those who enjoy period drama at a distinctly tepid temperature: for those who are perfectly fine with a film with the political momentum of a pinprick, rather than a stab at the heart.

–Claudette Palomares, November 2015

Suffragette opens in Australian cinemas 26th December (Boxing Day), 2015.

So, I’m interested to hear these perspectives but I just want to chime in with a few words of defence for the film. It’s not perfect, but IMO it still succeeds in bringing a largely untold story – of a working-class Suffragette – to the screen, and presenting it in a way that aims to engage a wide range of viewers. To say it is ‘an appeal to the emotions as a way to induce sympathy for the early feminists’ and to categorise it as a historical melodrama is accurate enough, but rather than seeing this as a weakness I think it’s one of its strengths (albeit a limiting one). The idea that the story of women’s fight for liberation in the UK should be the subject of a blockbuster film – schlocky though that genre tends to be – excites me far more than if it were the subject of a more arty, obtuse or challenging one. Also, I have to say how disappointed I am that there has been so much liberal backlash against this film because of its lack of non-white characters. I don’t agree that if you are ‘taking the moral high ground’ you ‘gotta go all the way’. For a story to be worth telling, I don’t think its protagonists have to live up to an ‘ultimate standard’ of victimisation. Inserting token non-white faces into a crowd scene wouldn’t have improved it for me. Unless there is evidence that the film-maker deliberately removed non-white characters from scenes in which they would historically have been present then I don’t think she’s done anything amiss in not covering this aspect of the movement – as you point out, it really is only a very partial view. Just to be clear, I am really interested to hear about the life of Sophia Duleep Singh and other non-white Suffragettes, I’m just tired of hearing this film being held up to critical and ethical standards that I think are a bit extreme and somewhat incoherent. The fact that it is directed by a woman (as very few big-budget films are) just makes me feel even more grumpy. Anyway, keep up the good work on the site (i’ve been reading the other posts with interest) and feel free to tell me why I’m wrong!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feminism always had the good and the bad, yet no one realizes this. I’m glad this movie actually shows the reality that these women had to face so white women can have their rights that they felt they needed. I hate to say it though, feminism was a middle class, white women’s club because they screamed the loudest for their problems, screw the lower classes and minority women that wanted their rights as well. 😉

LikeLike