Contents

WHO GETS TO SPEAK AND WHY? by Gabriella Edelstein

THE BOGEYWOMAN by Claudette Palomares

~

~

WHO GETS TO SPEAK AND WHY?

By Gabriella Edelstein

‘WHO GETS TO SPEAK AND WHY?, I wrote last week, IS THE ONLY QUESTION.’

– Kris Kraus, I Love Dick (1997)

It was in 1848 that the Brontë sisters revealed to their publishers that they were the writers Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Their individual works were being conflated under the banner of one “Mr Bell”, and the sisters felt they deserved their independent dues. Who can imagine what those sister-geniuses Emily and Anne were feeling in their long coach ride down to London, planning to unmask themselves to their publisher? Charlotte continued to publish under her pseudonym, even though it was well known in literary circles just who Currer Bell was. One night, at a dinner party, the novelist Thackeray met Charlotte, and addressed her as Currer Bell. In typically acerbic style, Charlotte responded, ‘I believe there are books being published by a person named Currer Bell… but the person you are talking to is Miss Brontë – and I see no connection between the two.’ In Charlotte’s mind, there was a distinction between the person Charlotte Brontë and the writer Currer Bell. This is not so different to a current trend in Karen Blixen studies, where critics either write on Karen Blixen, who they perceive as separate to her pseudonym Isak Dinesen.

Karen Blixen had several pennames, but Elena Ferrante only has one. And her one name has caused such a disruption in the hype machine media because of an adamant refusal to reveal what, or who, is behind it. Foucault, in a speech called “What is an Author?” asked, by way of Beckett, “‘What does it matter who is speaking,’ someone said, ‘what does it matter who is speaking.’” Foucault asked this question to interrogate why the author means so much in our culture, and whether a text needs an author to have meaning. Indeed, can we allow the meaning of Jane Eyre to be separated from the biography of Charlotte Brontë? Foucault devised the term author function to consider why it is that the writer of a group of books with similar characteristics are written by an “author”, and thus accrue status, but someone who composes, say, a blog, is just a writer. The author manifests discourse, which is of more worth to our society than a few insouciant lines somewhere on the Internet. The singularity of the author is much more appealing than dispersed, or anonymous, authority.

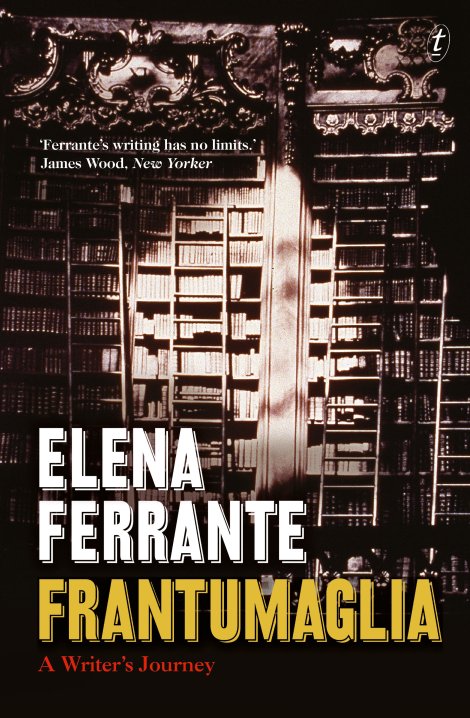

The phrase author function is sprinkled throughout Ferrante’s new book, Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, an updated edition of her 2003 book of collected interviews, letters and thoughts, originally published in Italian. She meditates on her recurring themes (childhood/motherhood, Ancient Greek mythology, dressmaking, Naples, the tension between heterosexual desire and feminism), edits the writing of the directors adapting her novels into films, and is sometimes snarky to journalists who ask the wrong questions. The book, taken in its entirety, reads like a long justification for why Ferrante has maintained her anonymity. And so long after the death of the author, I really do wonder, why does it matter so much to certain individuals who Ferrante is? Or perhaps, Foucault’s question should be altered to, “Does it matter that a woman is speaking?”. In light of the recent Ferrante doxing debacle, the answer cannot be anything but yes.

In one of the book’s many “Notes”, addendums to the piece you have just read, Ferrante’s editor Sandra Ozzola calls Ferrante’s project a ‘twenty-five year history of an attempt to show that the function of the author is all in the writing’. Frantumaglia, however, may protest too much. Ferrante sternly argues, at many points in the book, that the text is ‘a self-sufficient body, which has in itself, in its makeup, all the questions and all the answers’, and that an author is but a ‘devoted, diligent scribe, who draw in black and white following a more or less rigorous order of their own, but that the true writing, what counts, is the work of the readers’. For a writer who is clearly moving along the lines of a Foucauldian rejection of the author, Frantumaglia – which is an attempt to explain the absent author by way of (often repetitive) curated essays and unpublished letters – mounts the author back on her pedestal. There are notable voices missing from this book; for example, why are we not privy to exchanges between Ferrante and her translators? Ann Goldstein is the vehicle that has brought Ferrante to English-speaking readers, but she is curiously absent from the book, just as her name is absent from the covers of the various international editions. I wondered whilst reading, to what extent were the essays, articles and interviews chosen to create a certain imagine of Ferrante? She is front and centre and her editors and respondents gravitate around her, but cutting the translators from the picture is an erroneous depiction of how this book came to the majority of its readers.

The only way I can account for this book, if cynicism does not set in, is that the Ferrante project is one big, self-aware, radical literary experiment of whether an author can have no physical traces. This is especially progressive for a female author, who, typically, is beholden to her image. Instead, this author will not let others define her, only she can adumbrate herself in the eyes of the media, and only she can delineate the scope of her literary project. As she says in one interview, ‘I didn’t choose anonymity; the books are signed. Instead, I chose absence’.

It will no doubt be pointed out that there are discrepancies between the biographical information that furnishes the transcendent long middle essay in the book, and what we know of the person who is believed to be the writer of this book. But, is not the entire project of fiction an exercise in being someone else? The author, when they write, must become her characters to let them speak. What happens when this act of empathic creation leaves the boundary of the page and enters real life? We become irritated; I must admit, at certain points of reading, I wondered what the purpose of this book is. Why do we need to know anything about what Elena Ferrante thinks if all the meaning of her novels lie only in the novel itself? Perhaps, the point is, there is no point. The author continues to be absent even if there is empirical truth in her novels. So the game of cat and mouse continues, so we eagerly await another book.

—Gabriella Edelstein, October 2016

~

The Podcast

Download (Right-click and select ‘save as’)

(ANSA ALINARI)

~

THE BOGEYWOMAN

by Claudette Palomares

To prepare myself for Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, I decided to read Elena Ferrante’s earlier novel, Days of Abandonment. I was mildly terrified at the prospect. In an interview in Frantumaglia, Ferrante describes her literature as “a finger in certain wounds I have that are still infected.” Days of Abandonment—in its exploration of a woman’s physical and mental unraveling over the course of the eighteen days after her husband announces that he is leaving her for a much younger woman—represents more than a mere finger. To appropriate Ferrante’s metaphor, it is a novel that seems the literary equivalent of sticking a rusty pin into a festering lesion.

Yet despite the novel’s violence, or perhaps because of it, the book slowly wound itself around me, like a lock of hair encircled around a finger, so tightly drawn that it embeds itself into the skin. Even when I paused reading to do other things, I felt the winding; I was haunted by Olga’s dark fantasies and her ever-fading link with conscious reality. The book was a totem of hysteria and terror and, at the centre of it, was my own personal bogeyman.

The bogeyman is a bogeywoman. Her name is Poverella.

The poverella appeared to me first in My Brilliant Friend, where she emerged in the form of Melina, Lila’s aunt, a woman seduced and abandoned by the erstwhile poet and train conductor, Sarrotorre. Melina is dismantled by Sarrotorre’s rejection, she is no longer a woman, or human, in a functional sense. She spends her days in abstract grief, her wails the percussive soundtrack to the drama of Lila and Elena’s fraught girlhood. The most indelible image of Melina is that of her consumption of little cakes of soap, as if ordinary food is at once too good and too banal for this unloved woman and the largesse of her suffering. Yet in the epic scope of the Neapolitan Quartet, the poverella is a wisp, an emanation, while the drama of Lila and Elena’s lives envelops us, pulls us into the whirlpool until nothing but the raging current of their friendship remains. In contrast, in Days of Abandonment, the poverella is the fixed point of horror, she is the spectre that torments Olga and the reader. In her eighteen-day stupor, Olga hallucinates the poverella of Piazza Mazzini, the poverella of her childhood, the homeless woman who poisoned herself after her husband abandons her, as Olga’s would do to her, thirty years on.

As Ferrante describes in Frantumaglia, the poverella has seemingly haunted literature from the very beginning. She is Emma Bovary and Anna Karenina, Bertha Rochester and Dido. In Days of Abandonment, they are the broken “knick-knacks in the hands of their straying men.” The most familiar of these women, and the most extreme, exemplify the condition of hysteria: she is the consummate figure abandoned, the men she loves abandons her, and so too does reason. Yet this type of fragmented woman, while compelling, is not my bogeyman. As Dayna Tortorici describes in her review of Ferrante’s novels: “These stories are fine, but not always for me; like Olga, I have too much pride to embrace the type.”

The poverella that Ferrante offers in Days of Abandonment is far more terrifying, because she feels much more accessible, more possible. Ferrante’s poverellas are women, like you and I, and women that we know and love. We have read Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina, or their stories have seeped into our skin in unconscious ways. We are familiar with the tropes. We understand the insidious, trenchant snares of patriarchal norms, and battle against them, yet it is not enough. In Frantumaglia, Ferrante elucidates this thought:

My women are strong, educated, self-aware and aware of their rights, just, but at the same time subject to unexpected breakdowns, to subservience of every kind, to mean feelings.

We think that if we are educated, if we are feminist in largely everything we say and do, that we have inculcated ourselves against this unraveling, that we will not be undone by love, that we are invulnerable. Elena Ferrante reminds us that this is not true, it is a lie we tell ourselves. We are always susceptible, the possibility of destruction remains within us. It is a chilling thought.

For myself, the most haunting aspect of Ferrante’s poverella points to a more basic fear, that of the ultimate fate of the single woman, or in other words, the unloved woman. Even in a society seemingly liberal and progressive as Australia—the country where I live—this fear remains palpable. Our economic infrastructure: where single women are being priced out of the city when single men can still afford the luxury of living in urban communities, where the rate of homeless elderly women rises, show that the single woman is still often, if not always, an outsider perceived as a symbol of deprivation, rather than agency. In her illustrations of unloved women, Ferrante gave words to a quiescent fear that I was only dimly aware of: my fear of being alone, of being homeless, of the poverella.

It is no co-incidence that the poverella sounds like a sly perversion of Cinderella, the central narrative of romance novels, and of so much fiction marketed to women, not just in a literary sense, but every conceivable channel. Yet Ferrante, at every turn in Frantumaglia, warns us that not to give into that myth. In Frantumaglia, a journalist, Rachel Donadio asks Ferrante what “The best thing that you hope readers could take away from your work?”

Ferrante tells her this:

That even if we’re constantly tempted to lower our guard—out of love, or weariness, or sympathy, or kindness—we women shouldn’t do it. We can lose from one moment to the next everything we have achieved.

It is an answer startling in its ferocity. What to do with such cynicism, and what does Ferrante mean, when she knows that to live as she suggests would make a life untenable? Like her overarching project of anonymous autobiography, Ferrante wants us to eschew pat solutions and domesticable answers. Ferrante asks us, not to live in a life without love, but to live it unveiled, and with clarity. In Frantumaglia, Ferrante writes warmly of surveillance, which is a word that she suggests in unfairly linked with the concept of the voyeur, when it in fact represents a sense of vigour, of watchfulness, “an eagerness for feeling alive.”

According to Ferrante, women should use their natural capacity for surveillance as a form for self-care, understanding that the roiling blackness within us is at once personal, but also universal. She suggests that it is this tension, this oscillation between fury and love, which both marks, and dignifies, a woman’s life.

As Ferrante describes, in comparison to men, “who rule broad territories in the sun”:

Women still entertain ghosts, we have long experience with exhausting secret negotiations with revenants that sink their teeth into you as they caress you, and we don’t void them, we know that they are true inhabitants of that tangle of veins, blood, liquids, flesh that is our body.

Ferrante is the bogeywoman. I am the bogeywoman.

Share The Dignity

—Claudette Palomares, October 2016

Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey by Elena Ferrante

Paperback, 374 pages, Text Publishing (AUS edition), Europa Editions (ROW), ISBN: 9781925240009

Kinokuniya (Sydney) | Dymocks | Abbeys | Readings | Book Depository

If as suggested in the Podcast, ‘Elena Ferrante’ is a fictional construct, then it follows that Frantumaglia is a work of fiction.

But Frantumaglia has been presented as work of non fiction. As such, why should assertions within it, including the authors identity and life history not be interrogated?

LikeLike